Brig. Gen. William Troy

Tolbert

January 6, 1934 – September 16, 2021

Born: January 6, 1934, Hollandale, Mississippi

Died: September 16, 2021, Valdosta, Georgia

Education: Bachelor Of Science, Mississippi State University, 1955

Military: Brigadier General, United States Air Force,

GCI Controller, General’s Aide, Instructor pilot, Fighter pilot, Squadron Commander, Wing Commander

Rating: Command Pilot, Instructor Pilot

Aircraft flown: Piper Super Cub, T-6, T-33, F-4, F-15, F-16

Awards: Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross with oak leaf cluster, Bronze Star, Meritorious Service Medal with oak leaf cluster, Air Medal with 17 oak leaf clusters, Air Force Commendation Medal

Wife: Louie H. Tolbert, née King

Children: Terri Taylor, Tracie Harris, and Michael Tolbert

{ Part 1 }

On the Mississippi Farm

Troy, second row left, with his high school graduating class

William Troy Tolbert was born in 1934, in Hollandale, Mississippi, near the Mississippi River and in the middle of “cotton” country. Born a Mississippi farm-boy, few would have thought that his life would have taken him off his parents’ farm to a career in the United States Air Force as the commander of three fighter wings and culminating in his promotion to Brigadier General.

When he was born in Hollandale, it appeared that the destiny of the first-born of six children would be to spend a lifetime working with his parents on their farm, tending to the hogs and cattle, and working in the fields raising cotton. As he matured his mother saw the intellect in him and encouraged Troy to read and study well. His father instilled in him a work ethic and the knowledge that many goals can be attained by desire and perseverance.

Having to work on the family farm during World War II introduced him to captured Axis soldiers who spent their days as prisoners of war working on the Tolbert farm. When these German and Italian prisoners first arrived, he remembered that they were held in camps surrounded with barbed wire and guarded by sentries in towers manning machine guns. As the war ground on, the prison gate was left open, and the machine gun toting guards disappeared. Young Troy saw that the prisoners were people who were happy to be away and safe from the horrors of combat. He also saw many of them cry when they had to leave for home at the war’s end having gained a love for their temporary residence in the United States.

Those years working on the family farm also gave him an empathy for persons of color, who worked for his father as tenant farmers. He played with the black children and went fishing and hunting with their parents. Years later he understood why their children took separate busses to school, a matter which confused him as a child. Having to work with others of different ethnic and racial backgrounds made him a more kind and understanding person. His father’s admonition to “always remember your roots,” imbued him with a sense of humility that endured in his later years as a commander and General in the military.

In 1948, 14 year-old Troy Tobert looked to the sky after a summer day driving a tractor and plowing the cotton fields. He spied an airplane high in the sky and vowed that that was where his future lay. Previously he had flown several times in a friend’s family airplane and once in the chemical hopper of a crop duster. The fact that the friend and the friend’s father had both died in a mid-air collision, and that the crop duster ride was spent with closed eyes trying to keep the pesticide from totally engulfing him, would not deter him from his quest to soar in the skies. Besides, as he reasoned, it had to be a lot cooler up in the sky than driving a tractor on that hot dusty day.

Troy with sister Jo Anne on the farm’s donkey

{ Part 2 }

New Horizons in College

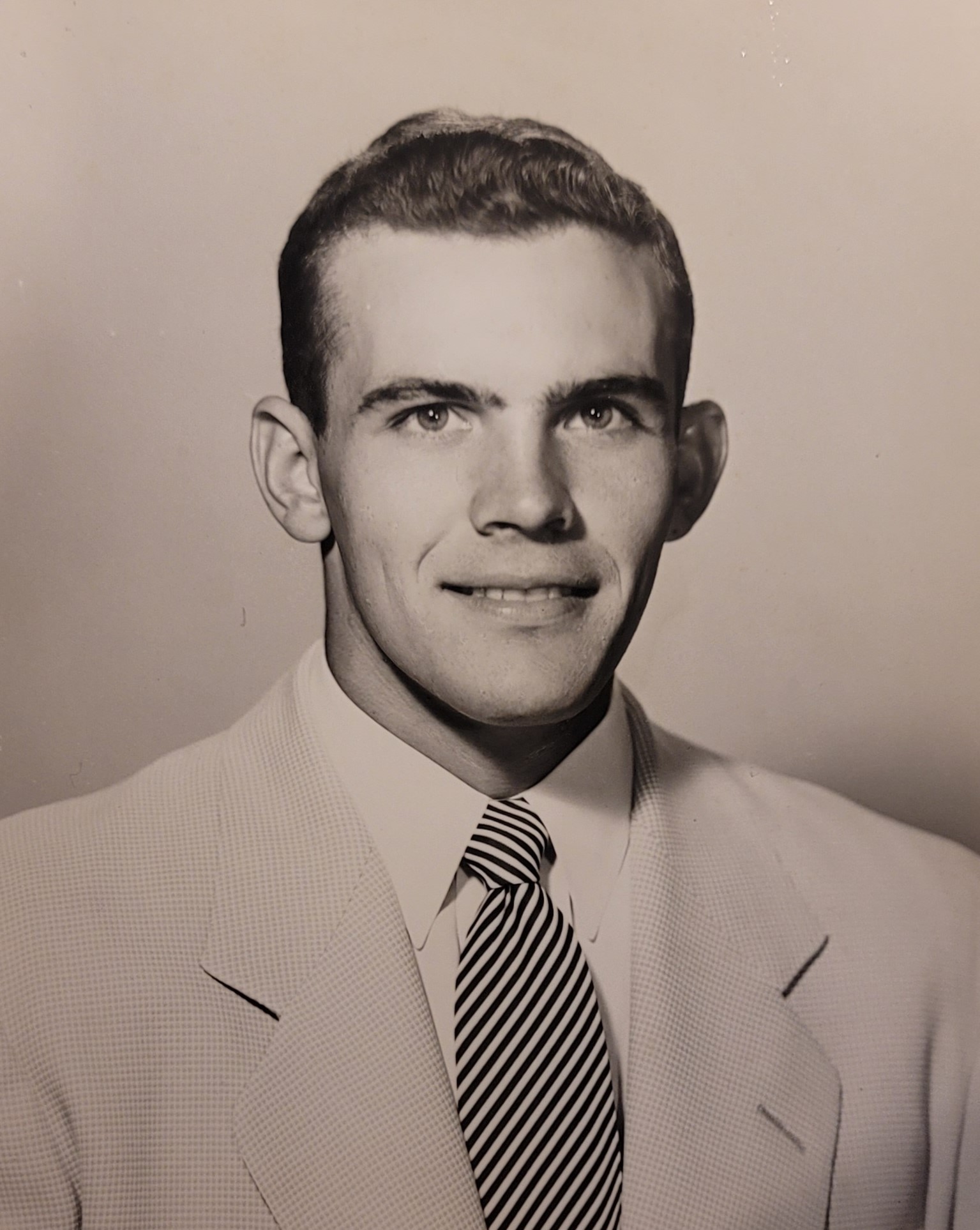

Troy – the Mississippi State University graduate

a member of R.o.t.c. at Mississippi State university

Troy was an avid football player excelling on his high school team, as he had been honed into shape by his farm work. Although he had suffered an injury to his neck and spine in practice in his senior year, he was offered football scholarships by both the University of Mississippi and Mississippi State. Mississippi State was Troy’s choice because a young lady with whom he had become enamored enrolled in a women’s college 20 miles from State. His coach and parents chose Mississippi State for Troy, because his scholarship would be honored even if he was again injured and couldn’t play football.

Even before football practice commenced before the fall semester started, Troy’s flame left the near-by women’s college and enrolled in another school miles away from State. His disappointment and heartbreak at her leaving were little comforted by his father telling him, “Don’t get upset over one as they are just like utility poles. There is another one down the road.” Her leaving and another football injury suffered at the beginning of his sophomore year focused Troy on academics and involvement in Reserve Officer Training Corps (R.O.T.C.) at State.

His social life brought him to a date with another Southern belle who soon captured his heart. It was in his junior year that he met Louie King with whom he fell in love. Their romance blossomed, and he soon met Louie’s mother who graciously accepted Troy. Louie’s mother was a widow and a true “Southern lady” who raised three daughters on a teacher’s salary. Louie endeared herself to Troy’s father by playing “truck driver” while he and Troy stacked the hay as she slowly drove it through the field.

Participation in R.O.T.C. brought him closer to realizing his desire, made on that tractor years before in that hot dusty field, to chart his future in the skies as an Air Force officer. The walls of the R.O.T.C. building were adorned with pictures of combat aircraft and distinguished airmen, which imbued him with a sense of patriotism that he had seen exhibited by those aviators returning from the War. Troy was particularly intrigued by photographs of Air Force generals little knowing that he would one day join their ranks.

In 1955 completion of his studies at State and R.O.T.C. earned him a commission in the United States Air Force as a Second Lieutenant. Louie had graduated the prior year, had turned down an offer to fly as an airline stewardess, and took a job in her home town working for the local gas company. She spent the year living with her mother and grandmother awaiting Troy’s graduation from Mississippi State. Soon after graduation, Troy received two of the three things he wanted most: he married Louie on June 5, 1955, and he received his officer’s commission. Now he was set to work for the pilot’s wings he had wished for on that hot summer day in 1948.

{ Part 3 }

Marriage and A Budding Career in the Air Force

Troy and Louie. . . newlyweds on June 5, 1955

PILOT TRAINING

After their wedding, Troy departed for San Antonio, Texas, where he learned how to march and how to act as an officer. After six weeks, Troy reunited with Louie and they were on the move to Kinston, North Carolina, for the start of flight training. Louie became Troy’s study partner reading all of the manuals with him, as he learned the book part of flight training. The training flights started in a 150 hp Piper Super Cub and progressed to the 600 hp T-6 Texan.

One of those training flights found Troy landing on a farm so that the instructor could check on his workers. Troy’s farm experience assisted him as he had to land the Super Cub into the wind. Troy determined the wind direction because while working on his parents’ farm, he knew the cows always stood with their rears to the wind . . . a convenient weather vane for a low and slow flying Super Cub. Transitioning to the more powerful T-6 brought more speed and a nascent desire to fly in the fastest and most powerful of the Air Force’s aircraft. Troy now set his sights on flying fighter aircraft.

A new instructor regaled Troy with stories of him flying combat in the F-86 fighter jet in Korea. Troy appeared early one Saturday morning in front of Base Operations at the insistence of the fighter pilot. At the designated hour the instructor made a high speed pass in his Air National Guard F-86 flying low just above the tarmac. After screaming over the runway, he pulled the fighter jet up into an almost vertical climb disappearing from sight. Any notion that Troy might have had to be anything other than a fighter pilot disappeared that day.

His flight skills and competitive spirit earned him a place at the top of his flight classes. They also determined where he would soon next go in his flight training: that being a slot at Webb Air Force Base in Big Spring, Texas, to train in the T-33. Troy was now out of propeller driven aircraft and had made the transition into one of the first jets flown in the Air Force. The T-33 was the trainer version of the F-80, which was one of the first Air Force fighter jets. Troy was now totally hooked on fast aircraft and the desire to become a fighter pilot.

His aspirations to become a fighter pilot were soon delayed. Although he graduated high in his flight class, he wasn’t high enough to get one of the two fighter assignments. His high scores and flight proficiency did nab him an instructor’s position which was spent training new pilots at Webb Air Force Base. Although disappointed about not going into fighters, the instructor assignment was a plus as it allowed Troy and Louie to settle down for four years from the whirlwind of Air Force assignments that came after their wedding. It brought them new friends and allowed Troy to hone his flying skills, which he would eventually use as a fighter pilot.

Troy was assigned as a Stan Eval Officer at Tyndall AIR fORCE bASE

THE FLIGHT INSTRUCTOR AND GCI OFFICER

Prior to working as a flight instructor, he spent three months at Craig Air Force Base in Alabama learning how to instruct student pilots. Returning to Webb Air Force Base, he went through another instructor training course and was finally given his first two flight students. He remembered the two as being too cocky, which could get them in trouble while flying. Troy gave them both a blindfold drill whereby they were to identify the location of switches in the T-33’s cockpit by memory. Mastering the skill was necessary for preparation for in-flight emergencies. Both students flunked miserably, suffered a blow to their egos and instilling in them some humility which served to make them better pilots.

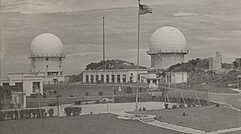

After four years as a pilot training instructor, Troy was assigned overseas to the island of Miyoko Jima, the “rock,” as a Ground Control Intercept (GCI) officer. Before being sent to the “rock, he was schooled at Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida on how to do intercepts of Soviet bombers. He took some solace knowing that he could still fly several times a month to maintain his proficiency. However, that did not compensate for a lack of daily flying and more importantly, having to leave Louie behind.

The highlights of Troy’s tour on Miyoko Jima, were observing the dome checks made by interceptor pilots in F-102s, making high speed passes in their fighter aircraft over the radar dome ostensibly “checking” for missing tiles. Another was being in the middle of a hurricane and seeing the base fire station being blown away with a fire truck still inside.

The last highlight came after seeing a Civil Air Transport C-46 transport aircraft damage one wingtip while taxiing. Undeterred, the pilot had a maintenance crew remove the last four feet of the wings so that he could depart the Miyoko airstrip. The transport pilot, who was experienced and had 20,000 flying hours, muttered to Troy and his colleagues in broken English before taking off, “Hell, I don’t need all that wing surface anyhow.” That was the practical part of flying.

After a year on the “rock,” Troy was reassigned back to Tyndall Air Force Base to serve as a GCI instructor. This assignment allowed both Troy and Louie to buy their first house, contemplate starting a family, and engage in the perks of living in Florida. After teaching for three years, he was also given a job as the standardization and evaluation officer which kept him flying and ensuring that the other assigned officers maintained their flight proficiency.

The radar domes at Miyoko Jima

troy serving as a general’s aide

Total fulfillment: an air force career, his wife louie, and their three children

THE GENERAL’S AIDE

Being the Stan Eval officer also brought him an interview with General Burns, who was the Division Commander, who offered him a position to become the General’s aide. Three months into the job, the General was promoted to Major General and assigned as the Commander of the United States Air Force mission to Pakistan. The General soon departed for Pakistan, on the opposite side of the globe from Florida. Troy followed weeks later as he had to get both Louie and the General’s family overseas safely to their new assignment.

Arriving in Pakistan while escorting both Louie and the General’s family, Troy endured the first of a number of crises. Just prior to their arrival, the General had suffered a heart attack. The General survived and soon after Troy and Louie had moved into a home with a half dozen servants in Karachi, Pakistan, the second crisis occurred.

The General was summoned to Rawalpindi to meet with the American Ambassador, where the General was informed that war with India would start at midnight. When Troy asked what they should do, the General, who had served in combat in World War II, said he was going to go to bed at their hotel. After the bombs started falling just after midnight, Troy and the other pajama-wearing guests who fled their rooms sought shelter outside the hotel. They spent the night freezing outside as the general enjoyed his sleep.

The third crisis came when the American State Department wanted the military to evacuate the United States citizens from the war zone. This task fell upon General Burns who with Troy planned and managed military transport for the citizens. A problem arose while the evacuation was underway. An attempt was made by Pakistani airport officials to block the aircraft with fire engines. The East Pakistani officials were not to allow the Americans to leave without properly going through customs.

On the General’s orders, the pilots of the Air Force C-130 transport aircraft loaded with the American evacuees had to play a game of “chicken” with the Pakistani authorities. While taxiing to the runway, the C-130s accelerated down the taxiway with lights flashing and engines roaring causing the operators of the fire engines to drive off the tarmac lest they be hit by the oncoming aircraft. The Americans were successfully flown out of harms way in an airlift planned and managed by the General and Troy.

After the initial crises, the deployment to Pakistan became more routine. The most memorable and exciting event came in December 1966 when Louie gave birth to Terri, the first of their three children. Louie and Troy showed their appreciation to the Catholic nuns who ran the hospital where Terri was delivered, by presenting them with a turkey and ham purchased from the Embassy’s stores. Three months later brought a return to Florida as General Burns’ posting to Pakistan was terminated. After several days visiting in Mississippi, Troy returned to Tyndall Air Force Base for his new assignment.

He was now assigned to MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, to learn how to fly the F-4 Phantom II. Troy’s dream was now to be realized, as he was to become a fighter pilot in the F-4, which was then the world’s finest fighter aircraft. At MacDill, Troy learned how to make the F-4 a lethal flying machine. There he was taught air-to-air combat skills and bombing techniques by instructors, who had flown in combat in Vietnam. Flying the Phantom was the realization of that dream started in that dusty field in 1948.

{ Part 4 }

The Fighter Pilot and Commander

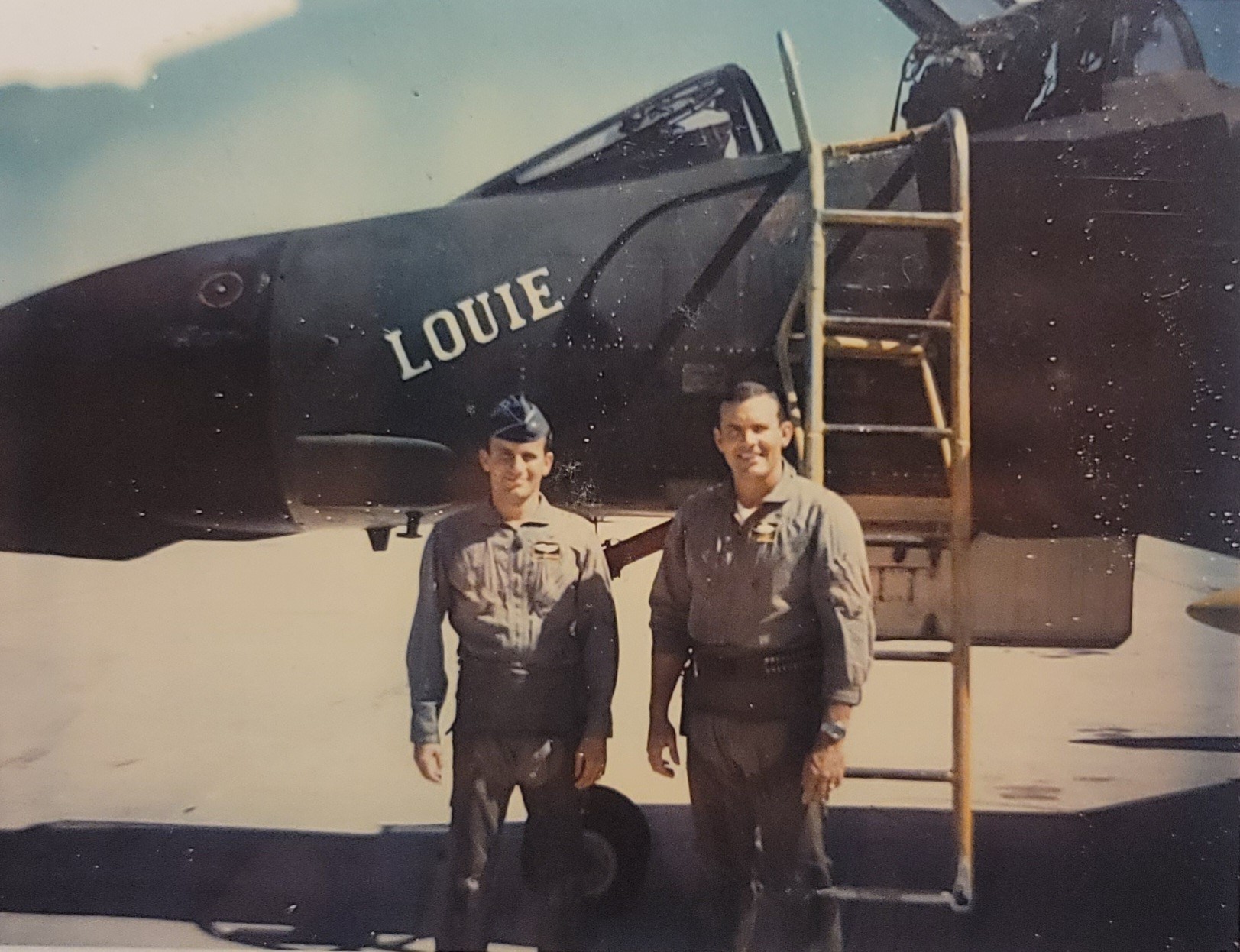

1968 – Troy in vietnam with his fighter jet named after his wife

celebrating Troy’s last combat mission flying out of Cam Ranh Bay Air Base, Vietnam

COMBAT IN VIETNAM

Before Troy could go to combat, he had to complete a number of Air Force survival schools. To him, these were not chores but extensions of his spirit of adventure cultivated as a Mississippi farm boy. These included sea survival training at Homestead Air Force Base in Florida, basic survival training at McCord Air Force Base in Washington, and while on his way to Vietnam, jungle survival training at Clark Air Base in the Philippines.

He took Louie and Terri with him to Washington state making it a family vacation while he worked on his survival skills. When they departed from Washington to return to Mississippi, they returned in their travel camper. Awakening to find the camper surrounded by buffalo was one surprise for the family. Later, having to stay snowbound in a post office parking lot for two days also made the trip memorable.

Getting Louie and Terri back to Mississippi and seeing their families before departing for Vietnam was depressing for Troy. Shortly after arriving in Mississippi, he was delighted to find that Louie was pregnant with their second child. However, his joy at becoming a father again was muted thinking that Louie would give birth while he was away at war. However, by sheer luck, he was on temporary duty from Vietnam to the United States when his second daughter was born. Troy was able to meet Louie in New Albany, Mississippi, where she was staying with her mother, when Tracie was delivered.

When Troy finally arrived in Saigon, Vietnam, en route to an assignment at Cam Ranh Bay Air Base, his part in the war was to start in earnest. He arrived in the South Vietnam capital in late January 1968 which coincided with the start of the communist Tet Offensive.

The first day in Saigon was spent in a building, which served as housing for approximately three dozen American aircrew members assigned to the local Tan Son Nhut Air Base. When the communist attack started, the flight officers, including Major Tolbert, were given handguns to “protect” themselves. All contact with the Air Force officials at the airbase was lost until the aircrews rescued an abandoned army jeep which had an operable radio.

When their calls for assistance were finally answered, an Army patrol consisting of two tanks and a half dozen armored vehicles was sent to rescue them. Led by a no-nonsense United States Army Captain, the communist attack on the flyers’ compound was neutralized, and the aviators transported to the local air base. Unfortunately, in that two day introduction to the war, Troy saw two Air Force officers killed, one sitting next to him while seeking shelter from enemy fire behind a wall atop their building, and the second who had sought cover downstairs. Troy was on the roof with binoculars trying to pinpoint the communists attackers’ location when the other officer was killed.

Troy also saw the stark reality of war, where the quest for survival trumped any semblance of dignity. The Army Captain paid no heed to the rank of the airmen telling them what to do and how he and his troops would get them to safety. He also told the aviators’ commander, a Lieutenant Colonel, that removing the dead bodies was the Colonel’s responsibility. When the corpse atop the roof could not be taken down via a stairwell, the army troops solved that problem. On the Captain’s order, the body was unceremoniously lowered to the ground by a rope tied around its neck and feet. Both deceased officers’ bodies were then driven to the Tan Son Nhut Air Base tied to the front of the armored vehicles.

Told to get into the armored vehicles without their luggage or personal items, one young lieutenant protested. Saying that he had just bought a new stereo system, the Army Captain told him that he could stay with his stereo if he wanted. With death staring at him, the lieutenant opted to get into the rescue vehicle with only memories of his precious stereo accompanying him to the air base.

For Troy, getting to Cam Ranh Bay Air Base and starting to fly combat missions in the F-4 Phantom II was easy stuff after that first day in Saigon. While flying out of Cam Ranh Bay, he flew the majority of his missions in support of Vietnamese and American ground troops. These were the most satisfying missions, as he knew he was helping troops who were under fire by the communists. They were also the most hazardous as their bombs had to be dropped with precision at low altitude making his F-4 vulnerable to enemy ground fire. Because the “friendly” ground troops were then usually fighting close to the communist troops, one had to be especially careful not to drop bombs on the “good guys” by mistake.

Due to them having to fly so close to the ground, the Phantoms returned from many missions with bullet holes in their fuselage or tail. Returning after one mission, the crew chief pointed out to Troy a bullet hole at the top of his ejection seat. The bullet had missed its target, and Troy’s head, by mere inches. Troy mused that he was happy that the enemy gunners were unlike the quail hunters from his youth, who knew how to lead their target.

Later missions took him flying to interdict truck traffic, while the North Vietnamese were moving men and military supplies out of the North in support of the communist troops in the South. Bombing missions to cut the roadway from North Vietnam into Laos through the Mu Gia Pass were made on an almost daily basis. The F-4’s bombs would make the roadway impassable during the day, and thousands of North Vietnamese laborers would refill the bomb craters that night so truck traffic could resume again. Occasionally, some flights were over North Vietnam attacking military targets in the communist homeland.

On one of his missions over North Vietnam, his aircraft was struck by a Soviet-built SA-2 surface-to-air missile. His Phantom had taken hits to one engine and to the vertical stabilizer making the damaged aircraft extremely difficult to fly. He nursed his crippled F-4 south to Da Nang Air Base, where he landed wheels up as his Phantom had also lost hydraulic pressure necessary to lower the landing gear. The beaten Phantom was not repairable and left at Da Nang to be cannibalized for spare parts.

In 1972 while stationed at Seymour-Johnson Air Force Base in North Carolina, he deployed again to fly in Vietnam with the 335th Tactical Fighter Squadron. The squadron was to fly out of Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base in Thailand in support of the “Linebacker” operation. By order of President Nixon, the United States had commenced the wholesale bombing of North Vietnam to try to end the war. While stationed at Ubon, Troy flew the majority of his missions around Hanoi and Haiphong interdicting military supplies coming from China.

On one of his first missions, the first surprise was having to dodge an AIM-7 missile which was accidently fired at his flight of four fighters by an F-4 flying behind them. Things got better but no less hazardous on the missions over the northern part of North Vietnam. Every day found Troy and his fellow aviators being fired on by anti- aircraft artillery and SA-2 surface-to-air missiles, and being attacked by communist MIG fighter aircraft firing guns and missiles at the Phantoms. This lasted from July until the end of December 1972, when Troy and his fellow crew members from the 335th returned home to North Carolina. During his two tours of duty in Vietnam, Troy flew 355 combat missions.

Troy returned to Seymour-Johnson Air Force Base as the Operations Officer and within a year was named Commander of the 335th Tactical Fighter Squadron, a job aspired-to by most Air Force fighter pilots, and the first of his fighter commands. With his leadership, his squadron became the best in this Fighter Wing, and he was named the “Top Gun” for his flight skills. Notably, in 1969 while stationed at Seymour- Johnson, he had also become a father again as he and Louie now had their third child, a son whom they named Michael.

the f-4 wing commander. . . the first of three fighter commands

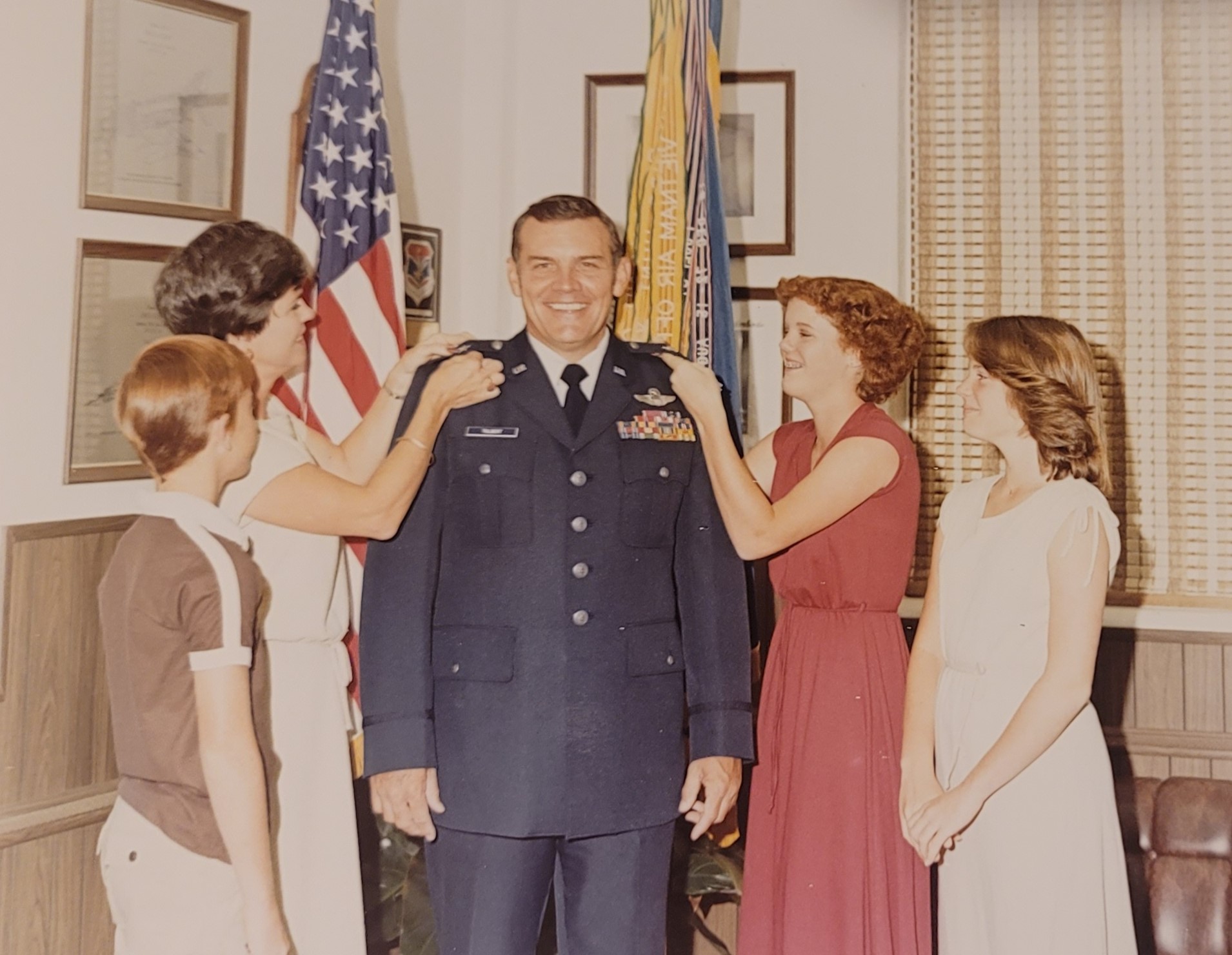

The new Brigadier General and f-15 wING cOMMANDER with his family

For his prior service accomplishments and for his success at Seymour-Johnson Air Force Base, he was rewarded by being sent to the Air War College from which he graduated in 1975. His next assignment was to the Tactical Air Command Headquarters located at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia. There, he was part of a group of combat-experienced officers who created “Exercise Red Flag.” This program sought to remedy the lack of success that the Air Force had in air-to-air combat while flying in Vietnam. Troy’s group developed a two-week advanced aerial combat training exercise held several times a year by the United States Air Force. Its aims were to offer realistic air-combat training for military pilots and other flight crew members from the United States and allied countries.

After holding staff positions at Headquarters Tactical Air Command and later Headquarters 9th Air Force, in 1978 he was appointed as Wing Commander of the F-4 Phantom II Fighter Wing located at Moody Air Force Base in Georgia. This was to be the first of three postings as a Wing Commander. . . an unheard-of feat in the Air Force.

At Moody, he took over a fighter wing that excelled but was micro-managed by its Commander. Troy changed the command philosophy by setting high standards but delegating decision-making authority to his subordinate commanders. He confessed that to be an effective leader, one sometimes had to be “lazy” or “hands off,” and expect more to be done by his personnel and their supervisors. By his leadership skills, morale at the base soared and the Wing excelled even more.

A year later Troy was assigned to Hill Air Force Base in Utah. There he transitioned from the F-4 Phantom II to the F-16 “Fighting Falcon,” fighter aircraft. The F-16 was later affectionately called by its aircrews the “Viper.” While he loved the “Phantom,” he considered the F-16 to be a “Maserati” with its superior climb and turn rates. Its fly-by-wire operation with a side controller eliminated the stick normally found between the pilot’s legs on the F-4, and the improved designs of its controls and the pilot’s seat allowed it to pull higher sustained G-forces necessary for air-to-air combat. During his year assigned as the first Commander of an F-16 Fighter Wing, he helped increase the flight effectiveness of the Viper and showed that it was ready for combat.

After less than a year in the job as the F-16 Wing Commander, Troy was ordered to fly to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico to be checked-out to fly the F-15 Eagle fighter aircraft. After five flights in the F-15, he was pronounced flight qualified, was promoted to one-star rank as a Brigadier General, and ordered to depart for Langley Air Force Base in Virginia to take over as Wing Commander. In less than two years, he was Commander of three Fighter Wings: he went from the F-4 Phantom II, to the F-16 Viper, and finally to the F-15 Eagle . . . all top-of-the-line fighter aircraft in the Air Force. (The position at Langley required a General Officer as Commander, so Troy went to his new position as a “frocked” Brigadier General.)

The assignment to Langley Air Force Base presented a unique problem as it was a showcase base, and the Fighter Wing had just flunked an Operational Readiness Inspection (ORI) which gauges the combat effectiveness of a military unit. Troy was told by his boss, a four-star general who was the Commander of Tactical Air Command (TAC), that either he shaped up the Wing, or he would be fired just like his predecessor. Further, not only was the Wing deficient, but the “showcase” base was in sorry shape.

Troy reasoned that while the aviators and the support personnel were qualified, they just needed direction. To do so, he immediately put the Wing on a combat footing by ordering all of the aircrew members to dress in their combat uniforms. His thought was that if he wanted his “people” to be warriors, they should dress the part. At a group meeting, he fired a Lieutenant Colonel, whose excuse for not wearing his flight suit was that his wife couldn’t find it for him. The rest of the officers got the message that their new Commander would not accept excuses for poor performance.

To get the deficient aircraft maintenance remedied, lunch and a “heart to heart” talk with the officer in charge of procurement remedied a lack of aircraft spare parts. To get more aircraft flying, he ordered the airmen to start 12 hour shifts until enough F-15s were combat ready. After several months, Troy asked his senior NCOs if the Wing was ready to revert back to an 8 hour day. When they said “No,” he left the long shifts in place until the maintenance supervisors said their airmen were ready for the shorter workday.

Within six months time, the Wing passed the ORI with flying colors and was deemed the “premier” Fighter Wing in TAC. With that accomplished, Troy’s next task included getting additional funding and man-hours to renovate the base. Being so close to Washington D.C., it was a favorite destination to show to visiting foreign dignitaries. With new monies and the new-found esprit de corps becoming the “top” Air Force Fighter Wing, the base and wing personnel gave the Base an upgrade and turned it into the showplace worthy of hosting Presidents and other heads of state.

{ Part 5 }

Retirement and New Pursuits

troy’s book written for his family

after 60 years together – Troy and Louie celebrating a granddaughter’s wedding

After serving the better part of five years as the Commander of three Fighter Wings, Troy and Louie decided that he had given the Air Force enough of his soul. After much searching, they decided that settling down in a new home in Valdosta, Georgia, was where they would enjoy their retirement. Valdosta was close to colleges that their children could attend, was close to both Louie and Troy’s families, and close to the convenience of Moody Air Force Base.

The children flourished now having a permanent place they could really call home. The location also meant that the Tolberts could spend more time with their families in Mississippi. After graduating from college, the children married and started their own families making Louie and Troy proud grandparents. With their children doing well, and after the years of constant demands put on him by the Air Force, life for Troy was now . . . comfortable.

However, while Troy could focus on his family, he found new challenges to occupy his time. With a friend, he helped expand a regional grocery and convenience store business. After years helping make it a success, he worked with another friend to create a hunting preserve. This was also successful and brought him back to the days as a youth and young man when he went quail hunting with his dad.

His biggest challenge was engaging the local community to fight the imminent closure of Moody Air Force Base. With other retired Air Force officers and local civilian leaders, the group was able to show a congressional delegation the exceptional worth of Moody to both national defense and to the local community. By their efforts, Moody was taken off the closure list and it presently remains an important asset to the nation.

In the midst of spending time with his family, starting and running businesses, and saving a military base, Troy found time to let the writer in him blossom. After months of effort, he completed a book detailing his life. From Dirt to Duty was published in 2008 and was written not to boast of his achievements, but to tell his children and grandchildren about his life: from his humble beginnings on the Mississippi farm, to flying in combat as a fighter pilot, and to becoming an Air Force general leading thousands of men and women in the nation’s defense.

Credits:

Author: K Giffard

Photos:

Intro: General Troy Tolbert

Part 1: 1940s Mississippi cotton fields

Part 2: Mississippi State University football team – Troy is No. 32

Part 3: Troy and family in North Carolina 1970s

Part 4: The F-4 Fighter Pilot

Part 5: Troy and Louie with their grandchildren